Unlocking the Value of “Hidden” Metals

The world of metal recycling is never straightforward, with sometimes the slightest market variable causing significant volatility in global trade. But throw Covid-19 into the mix, and like many industries, scrap became an even more complex place to be.

When the lockdown was first announced, certain countries, such as Italy, brought everything to a halt. Others saw reduced capacity, with only 40 percent of larger yards remaining operational in France, for example, and smaller to medium-sized sites closing their doors. Merchants were restricted by curfew hours in places like Saudi Arabia, while in the UK and USA, the industry was granted critical status, meaning yards could stay open. It was perhaps unsurprising to see such geographical variances, which added to the difficulties surrounding the movement of materials in the earlier weeks. There have certainly been periods of slower trade, but there have also been rallying cries for scrap businesses to get the credit they deserve for being the lifeblood of the resource sector.

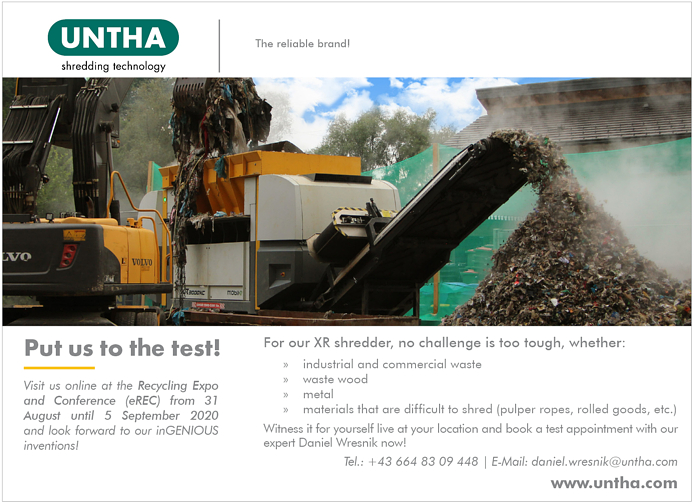

Peter Streinik, metal recycling specialist, Untha shredding technology (Photo: Untha shredding technology)

Our own – albeit anecdotal – conversations with the industry have revealed several large MRFs and metal recycling specialists pressing ahead with innovations when it comes to the handling of scrap. Because still, too much metallurgical content remains hidden or locked within redundant products, which continues to limit the amount of material salvaged for smelting. And some niche operators are determined to address this. They are looking to the future.

When it comes to composite materials within small and large domestic appliances for example – as well as many other types of WEEE/e-scrap too – the environmental and commercial advantages of liberating valuable metals is fairly widely acknowledged.

Effective material liberation strategies

That is not to say the process is straightforward or that recycling rates are always maximized. Many operators rely only on traditional, cumbersome shear equipment to cut metals down because the perceived high-wear nature of metal shredding is deemed too cost-prohibitive. However, dependence on this basic shear methodology means alternative sorting, grading, separation and size-reduction processes are overlooked and metal recyclate quality typically remains low as a result.

Machinery such as high-speed hammer mills – which work by smashing material into smaller pieces with repeated impact blows – typically create vast amounts of dust. This dust is useless, costly and it poses a fire and operator wellbeing risk. This process also struggles to achieve the particle refinement required for downstream separation technologies to effectively do their job.

Mindful of the limited revenue potential associated with these approaches, recyclers elsewhere are investing in more sophisticated processing lines complete with shredder, overband magnet to extract ferrous metals, eddy current separator (ECS) to separate any non-ferrous metals, and optical sorter to clean anything the ECS has not already refined. The greater the level of quality metals recovered, the higher the revenue potential. The recovery of high-worth platinum group metals (PGMs) and rare earth metals (REMs) could make for a particularly profitable operation.

“Undiscovered” metal recycling opportunities

Some operators are already familiar with such “best practice” metal recycling methodology, and are consequently exploring the market to see “what’s next?”. It is a good thing that they are searching for further opportunities because they do exist in the form of “wastes” that are notoriously tricky to handle. But with engineering advancements and clever process design, heightened recovery rates are certainly achievable.

Millions of bulky end-of-life mattresses are disposed of per year, in the UK alone, for example – with many of them being dumped illegally. But it is possible to size reduce 200 of these per hour with slow-speed, high torque and economical machinery. Then clean flock can be used for alternative fuels and the metal extracted for smelting. That is an important waste stream to get to grips with, considering the ambitious landfill diversion targets for mattresses.

But this is not the only tricky application where metal recycling potential remains untapped. The global waste industry is sitting up and paying more attention to tire processing, for instance, given the growing demand for tire derived fuel (TDF). However, a valuable by-product of a savvy tire handling line is metals, which would otherwise remain trapped in these bulky, toxic products. That is not all – one of our waste wood shredding clients is generating more than 3,000 British Pound (editor’s note: about 3,760 US-Dollar) of revenue per week from the sale of clean metals extracted directly off the magnet belt. The difference with these latter described applications is that they are renowned for being difficult and, as such, have long been avoided. But so many people are focusing on processing the “good” – or easy – material. Only by developing ways to treat dirtier or more complex materials will we be able to establish truly closed-loop models that turn more “waste” products into reusable resources.

(GR22020, Page 33, Author: Peter Streinik, Photo: Harald Heinritz / abfallbild.de)