E-Waste: Collection and Shredding Alone Are Insufficient

Why is e-waste recyclate quality still being overlooked, and what is the answer to best practice?

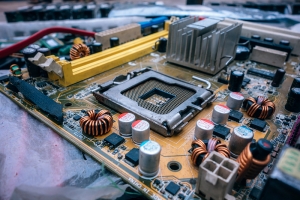

The recycling of e-waste is dominating the waste industry’s headlines at present, not least because updated legislation is continually coming into force. But there is more to e-waste (or WEEE) recycling progress than recovery rates alone. Marcus Brew, managing director of WEEE shredding specialist UNTHA UK, urges the industry to pay more attention to recyclate quality too.

E-waste is not a newly-regulated market. In Europe, for example, legislation has existed since the early 2000s to drive recovery progress, encourage producers to play their part, and to clamp down on illegal trade. Directive amendments have since stepped things up even further, primarily because the mounting “throwaway mindset” that modern society seems to exhibit, is adding extra pressure to an already challenging area of the waste arena.

In fact, because e-waste is one of the fastest growing waste streams in the world, it will probably be decades before the law begins to stand still. It has to adapt to reflect the growing variety of electrical equipment now available in the market for instance, which probably explains the need to recognize Open Scope rules. But the legislation will undoubtedly also become tighter over time if countries continually fail to reach the recovery targets set. The UK is just one of many culprits.

Given the movability of this legislative landscape, it is perhaps understandable why recovery rates dominate industry headlines. But there is more to understand e-scrap management than collection compliance alone.

It is important to consider what happens to recovered e-waste too.

It is crucial to ensure the ethical and professional handling of this inherently hazardous material stream by a specialist operator, for example. Globally, the illegal export of e-waste has been reported as a significant industry problem over the years, and the reason for this is probably two-fold. Firstly, many people simply do not know how to deal with this complex waste stream. So, in the face of targets they cannot meet, they ship the materials overseas so that they are someone else’s problem. Other people readily acknowledge the level of high-value precious metals that are locked away within e-waste, which leads to the second reason for illegal trade – people want to access, salvage and sell the gold, silver and palladium.

However, these catalysts for unscrupulous e-waste handling can have catastrophic consequences. If e-scrap is not managed by a competent, licensed facility, there is a risk that many of the inherently hazardous substances within e-waste could end up in the general waste stream. If water courses became contaminated, for example, this would put surrounding communities at significant risk. There have also been reports of children in developing countries manually handling these waste streams, which exposes them to these harmful contaminants.

Best practice

Assuming e-waste passes through a compliant supply chain, it is then important to think about the best-practice methodologies that should be executed to ensure the maximum environmental gain. In many cases, seemingly outdated e-waste can be refurbished for re-use, providing it is stored correctly prior to being handled – being left outdoors in a cage and exposed to the elements will only lead to quality deterioration. The equipment may be unwanted but still in perfect working order or suitable for resale following a safety inspection and repair.

Beyond that, maximum recyclate recovery rates should be the priority. An effective material liberation strategy should, therefore, be devised, so that the valuable commodities such as gold and copper can be extracted, segregated and re-inserted into the supply chain.

The manual breakdown of equipment, by trained professionals, is often the preferred methodology. This approach is admittedly labour- and time-intensive, however, the high-value nature of the materials inside means that this is usually a worthwhile exercise.

When it is not commercially viable to manually strip back the e-waste or gain access to all the component parts, a shredding operation can be designed to release these valuable recyclates. Some e-waste operators have traditionally opted for a hammer-mill machine, which works by smashing aggregate material into smaller pieces using repeated impact blows. However, such equipment is typically high speed, which can create a significant amount of dust. Not only is this dust useless and costly, but it can also pose a fire or operator wellbeing risk. Hammer mills also cannot usually achieve the particle refinement required for downstream separation technologies to effectively do their recycling job.

A four-shaft shredder with a screen, on the other hand, will systematically break the e-waste down to ensure the production of a homogeneous fraction. Ideally, the technology should be high torque and slow speed, for reduced dust, low wear, increased uptime and added efficiency.

For an extremely sophisticated turnkey solution, the operator should also consider the integration of an overband magnet to help extract ferrous metals, an eddy current separator (ECS) to separate out any non-ferrous metals, and an optical sorter to finally clean anything that the ECS has not already refined.

More comprehensive e-waste handling systems naturally represent more of an upfront investment. However, if driven by commercial factors, it is important to think about the likely payback and not just about the upfront price tag of the system. The revenue yield will soon cover the initial capital outlay. After that, everything is largely profit.

Then there is the “green” agenda to consider. E-waste is a staggeringly worrying problem on a global scale, and if its creation cannot be reduced at source, greater effort needs to be exerted to better manage it. E-waste can no longer be disregarded as someone else’s problem. The more that valuable “waste” materials locked within this “scrap” can be salvaged and re-inserted into new manufacturing processes, the greater the world’s resource security in an era of often dwindling raw materials.

Photo: Untha UK

GR 3/2018